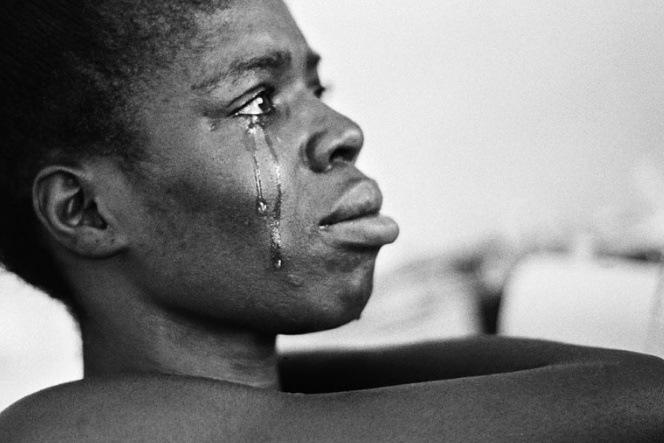

Five young Indigenous children have taken their lives in the space of a week, leaving their families and communities in a state of shock and grief.

January 2019 marked a month of horror for families across Western Australia, Townsville and Adelaide:

A 15-year-old girl from Western Australia died after just two days after self-harming on a visit to Townsville.

A 12-year-old girl died in a small town in Port Hedland named Pilbara.

A 14-year-old girl died in a small town in East Kimberly.

A 15-year-old girl died in Perth.

A 14-year-old girl died in Adelaide.

A 12-year old boy is on life support in Brisbane after what is presumed to be an attempted suicide.

This list is too long, and the grief for the families and communities of these children is unimaginable.

For the past decade, nearly 40% of child suicides were Indigenous children. These numbers are horrific, and as the National Coordinator for the National Child Sexual Abuse Trauma Recovery Project, Gerry Georgatos, has stated previously, “the nation should weep” for the harrowing tragedy of the deaths of these young children.

Federal Aboriginal Affairs Minister, Nigel Scullion, has stated that every suicide was a tragedy and the effects they have on tight-knit Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are profound.

These suicides reveal that a change must occur across our communities, as the deaths of five young Indigenous people in the space of one month is five too many.

We must be asking our leaders, our policy makers, the media, and anyone who will listen, what are we doing to change this? These children are more than just a disturbing statistic, they were young Australians who believed they had no other option than to end their lives. When will we start taking charge to initiate change?

The Director of Suicide Prevention Australia, Vanessa Lee, has called upon our federal government in an attempt to support and catalyze change in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander suicide prevention strategies.

“When are we going to see change … when are we going to see a national Indigenous suicide prevention strategy supported by the COAG, delivering for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people”, Ms. Lee asked.

Gerry Georgatos reflects on the impact that these deaths have on surrounding communities as well as the families of these young people. The deaths of these young girls and boys is not the end of a tragedy, but merely the beginning of the grief, trauma and suffering that produce a ripple effect to the people closest to the deceased.

Georgatos states, “These incidences have impacted the family. . . hurt them to the bone. There are no words for anyone’s loss.”

“To lose a child impacts (us) in ways that no other loss does, and to lose a child is a haunting experience straight from the beginning and doesn’t go away”, he continued.

The deaths of these young children come as Western Australia waits upon its final report from the coronial inquest into the 13 Indigenous youth suicides from 2012 to 2016 in the Kimberly region.

The Kimberly region had the highest rates of suicide in Indigenous people of all ages from 2012 to 2016.

State coroner, Ros Fogliani, is expected to publish the findings of the inquest early this year. Whilst we wait for this report, the deaths continue, as we’ve experienced with horror throughout January.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics found that Indigenous children aged between five and seventeen commit suicide at five times the rate of non-indigenous children. The ABS also found that one in four people who took their own life before turning 18 were Aboriginal children.

A senate inquiry in late December found that support services are severely lacking in remote and rural areas of Australia, which makes it difficult to find support for Indigenous people and children, but also that culturally appropriate services were often just not accessible at all.

The lack of culturally appropriate services has become a sticking point for leaving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples without access to appropriate mental health services.

The next question we must be asking is why are we not talking about these enormous losses? Have you seen anything in your Facebook feed about the epidemic sweeping through Australia, leaving grief in its path?

I question how we cannot be talking about these deaths and raising the awareness necessary across Australia communities. Did you know that the Kimberley region had the highest Indigenous suicide rate in Australia? I certainly didn’t. I didn’t read anywhere about the deaths of these young Indigenous children, nor did I see its coverage on television. Here we are in the midst of national crisis, and we cannot give the respect necessary to tell these girls’ stories and promote the change necessary to stop this morbid trend.

These children are more than just numbers, they are more than a sentence on the page and they deserve the attention of the Australian public. A change will not happen without the support of the Australian community in raising awareness about suicide prevention, to encourage our leaders to change our policies and to provide the means of support services to rural communities that truly need them.

University of Western Australia’s Pat Dudgeon stated:

“Governments need to do more to prevent suicide by including Indigenous people in their discussions. We also need to consider the social factors leading to these issues and the need for community-led, culturally based solutions.”

How can we fail these children in this way, and how can we start the change necessary to prevent these deaths into the future?

We must promote support for all Indigenous people and stop this trend, we cannot let the deaths of more Indigenous children go unnoticed. We should be talking about how to initiate change and increase appropriate support services.

*Any readers who are wishing to seek support or information about suicide prevention are able to contact Lifeline on 13 11 14, or the Suicide Call Back Service on 1300 659 467.